Tutorial

This page is a summary of a Protelis Tutorial lectured by Danilo Pianini at the 11th IEEE International Conference on Self-Adaptive and Self-Organizing Systems at the University of Arizona, in Tucson, on September 2017.

Tutorial in the saso proceedings

Workbench setup

This tutorial leverages the Alchemist simulator for executing Protelis programs in a simulated network of devices. Details on the simulator are out of the scope of this tutorial, in this tutorial we will only introduce the elements strictly necessary for configurating the device network.

Prerequisites

- Internet connection

- A working installation of Java 8+

- A terminal emulator

- Unix-like terminals are ok

- Should work also with the Windows cmd.exe

- Don’t ignore case sensitivity

- git (preferred), or a program to decompress a zip file

Download

-

In the following,

WORKSPACErepresents the folder you want to work into - Option 1 - git is installed on the system. Issue:

-

git clone https://github.com/AlchemistSimulator/SASO17Tutorial.git WORKSPACE cd WORKSPACE

-

- Option 2 - I don’t have git and I don’t know what git is and I have no time to learn it

- Download from: http://bit.ly/saso17tutorial-zip

- Unzip in

WORKSPACE - Open a terminal in

WORKSPACE

First run

Issue the following command:

- On Unix terminals:

-

./gradlew -Pfile=nothing

-

- On Windows Prompt:

-

gradlew.bat -Pfile=nothing

-

Expectation:

- Lots of downloads

- A graphical interface with a white background

Setup explained

The Gradle mini-box

Gradle is a (very trendy) build system based on Java and Groovy. We use it to:

- Download the software automagically

- Execute the Simulator

- It’s easier, quicker and more portable than using

shorjavadirectly

- It’s easier, quicker and more portable than using

- It reads what to do from the

build.gradleFile

build.gradle

// We will need Java

apply plugin: 'java'

// All the stuff can be found on Maven Central

repositories { mavenCentral() }

// We need the simulator at version 6.0.2 (change the number to test with newer versions!)

dependencies { compile "it.unibo.alchemist:alchemist:7.0.0" }

// OK that's a bit more complicated, but in the end just configures a Java process and launches it

task "run$file"(type: JavaExec){ // Create a new task with a dynamically discovered name (Groovy coolness)

classpath = sourceSets.main.runtimeClasspath // Put the simulator and its dependencies in the classpath

classpath 'protelis' // Put all the protelis files in the classpath (so the interpreter can find them)

classpath 'maps' // Cool stuff for the last example :)

main = 'it.unibo.alchemist.Alchemist' // Launch this java class

args(

"-y", "sim/${file}.yml",

"-g", "effects/${file}.aes",

"-e", "exported-data"

) // With parameters "-y sim/<SOMETHING>.yml -g effects/<SOMETHING>.aes -e exported-data"

}

/*

* If nothing different is specified, search for a property named "file" in the project, then run a task with such name.

*/

defaultTasks "run$file"

A simulated environment

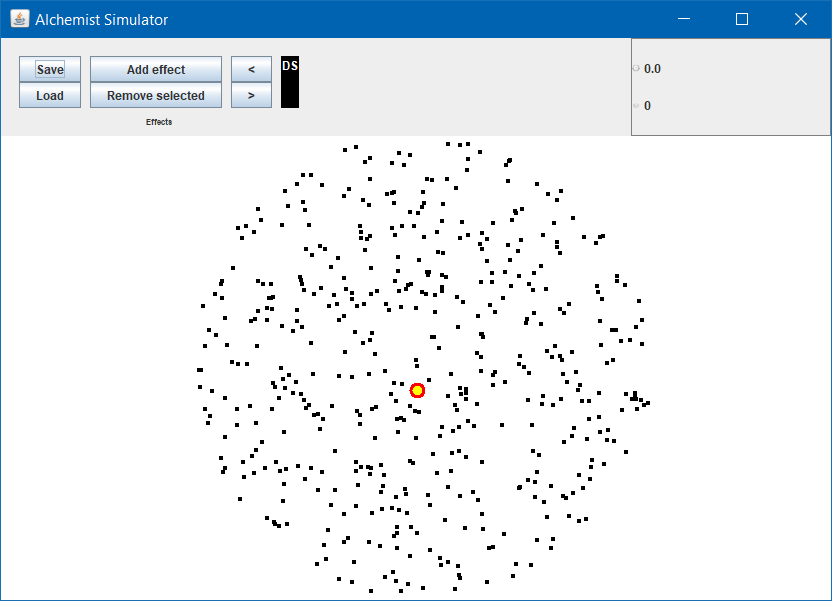

Let’s displace 500 nodes in a circle in a bidimensional euclidean space

00-devices-in-a-circle.yml

incarnation: protelis

displacements: # In this section we list our device displacements

- in:

type: Circle

parameters:

- 500 # Number of devices

- 0 # X center of the circle

- 0 # Y center of the circle

- 50 # radius

- Run with

./gradlew -Pfile=00-devices-in-a-circle - Expected:

Pan, zoom, node information

Let’s play a little bit with the graphical interface:

- Pan by left click + drag

- Zoom with the mouse wheel

- Rotate by right click + drag

The node closest to the mouse is marked with a yellow and red dot

- Double click to open a frame with the node information

- Position

- Content

- Programs to execute

- Press M on your keyboard to disable the marker

- Useful e.g. if you want to grab a screenshot

Manually moving nodes around

Nodes can be moved around by hand:

- The S key enters and exits the “selection mode”

- Enter in selection mode, select a group of nodes by dragging a rectangle around them

- Press O

- Drag the nodes to another position

Be wary that:

- Moving around is very useful for demoing and prototyping

- Moving stuff manually around will make your experiment non reproducible

- We’ll see other means of moving nodes and retain reproducibility

Drawing on screen in Alchemist

Alchemist supports the definition of a stack of graphic effects in order to use colors and shapes to understand what’s going on.

- Saved as a JSON file, that can be manually edited before launching the simulation

- The effects can be edited and saved from within the GUI

- The stack is applied one effect at a time

- Upper layers cover lower layers

- With some training, it’s possible to achieve nice results using transparencies

00-devices-in-a-circle.aes

[

{

"type": "class it.unibo.alchemist.boundary.gui.effects.DrawShape",

"curIncarnation": "protelis",

"mode": "FillEllipse",

"red": {

"max": 255,

"min": 0,

"val": 0

},

"blue": {

"max": 255,

"min": 0,

"val": 0

},

"green": {

"max": 255,

"min": 0,

"val": 0

},

"alpha": {

"max": 255,

"min": 0,

"val": 255

},

"scaleFactor": {

"max": 100,

"min": 0,

"val": 50

},

"size": {

"max": 100,

"min": 0,

"val": 5

},

"molFilter": false,

"molString": "",

"molPropertyFilter": false,

"property": "",

"writingPropertyValue": false,

"c": "Alpha",

"reverse": false,

"propoom": {

"max": 10,

"min": -10,

"val": 0

},

"minprop": {

"max": 10,

"min": -10,

"val": 0

},

"maxprop": {

"max": 10,

"min": -10,

"val": 10

},

"colorCache": {

"value": -16777216,

"falpha": 0.0

}

}

]

Network model

If we want the node to connect to each other, we must tell the simulator how to do so:

01-devices-connected.yml

incarnation: protelis

# Connect nodes that are sufficiently close

network-model:

type: EuclideanDistance

parameters: [10]

displacements:

# Expected: a YAML list of device displacements

- in:

type: Circle

parameters: [500, 0, 0, 50]

- Launch with

./gradlew -Pfile=00-devices-connected - Expected: same as the previous experiment

- Press L on the keyboard to visualize the network links!

- Try to move them (press S then select with the mouse, then press O and use drag and drop to move selected nodes around)

Alchemist can load any implementation of its interfaces

For each type of object written in the simulation file, Alchemist tries to find and build a Java object implementing a concrete version. The resolution is operated as follows:

- if type and (optionally) parameters are found as keys of the object, a class with the corresponding name is searched and a constructor is invoked with the provided parameters

- All parameters that can be deduced by the context are automatically bound (objects of type

Environment,RandomGenerator,Incarnation,Node,Reaction,LinkingRule) and must not be provided in the parameters list

- All parameters that can be deduced by the context are automatically bound (objects of type

- If the provided parameter is a string, it is forwarded to the current Incarnation for interpretation

- In any other case, a default system value is looked for If the lookup or the build fail, the simulation won’t get built.

To find out the available types and their constructors, refer to the Javadoc at: http://alchemist-doc.surge.sh/

My first Protelis program

- Now press P to begin the simulation

Uh?! Nothing happens… The time just jumps to Infinity.

- In fact, there are no events in this simulation :)

Let’s program the nodes with an extremely simple Protelis program: 0

02-0.yml

incarnation: protelis

network-model:

type: EuclideanDistance

parameters: [10]

displacements:

- in:

type: Circle

parameters: [500, 0, 0, 50]

programs:

- # This list of lists seems useless, it actually makes sense when you use YAML anchors

# Round frequency (advanced distributions can be used with the time/parameters syntax)

- time-distribution: 1

# This is the program we want to execute locally

program: 0

# This tells the simulator to share the results of the last computation. No time distribution has ``as soon as possible'' semantics (Markovian event with inifinite rate). The separation is useful in case the user wants to simulate a delay between the computation and the delivery of messages, e.g. to simulate network delays, or a battery saving policy on the wireless modules.

- program: send

- Run with:

./gradlew -Pfile=02-0 - Then press P to begin the simulation

Expected:

- The time flows!

- Nodes turn red

- I’ve configured an effect that changes color if the node has computed, it’s no black magic

- If you open a window with the node contents:

- In “Contents”,

0is associated todefault module:default program- It’s a Protelis-generated name for anonymous modules

- In “Program”, two entry appear: one is the round computation, the other one is the event sending information to neighbors

- In “Contents”,

- You can use P to pause and restart the simulation

Speeding up the simulation in Alchemist

Improve the performance

- If you attached a profiler to Alchemist, you’d see that most of the time is spent in rendering nodes

- By default, the simulator renders the entire scene (within the viewport) after every event

- This can get very expensive very quickly

- You can tune the refresh rate of the UI by pressing:

- Right arrow: speed up (less calls to the graphics)

- Left arrow: speed down (more calls to the graphics)

- If you speed up too much, the UI will become sluggish (e.g. if you update it only twice per second)

- R can be used to try to make the time flow linearly

- Useful in case of sparse, unevenly distributed events

- Left and right arrows keep working

Loading a Protelis file

- Writing Protelis specification within a YAML file is not what we want

- No portability

- Easy to make mistakes

- Horrible kludges to make YAML happy with pieces of Protelis inside

- Maybe you want to run your code elsewhere, not just inside a simulator

- Let’s load a Protelis program from its own file!

tutorial/zero.pt

// Make sure that the module is in the classpath!

module tutorial:zero

0 // Program script

03-load-module.yml

incarnation: protelis

network-model:

type: EuclideanDistance

parameters: [10]

displacements:

- in:

type: Circle

parameters: [500, 0, 0, 50]

programs:

-

- time-distribution: 1

program: tutorial:zero # Just use the name of the module! The loading happens transparently from the classpath (which, of course, means that your Protelis source folder should be included in your Java classpath)

- program: send

- Run with:

./gradlew -Pfile=03-load-module

Factorial in Protelis

tutorial/factorial.pt

module tutorial:factorial

/*

* The language is functional, every expression has a return value. In case of multiple statements in a block, the value of the last expression is returned.

*

* Comments are C-like, both single and multiline supported.

*

* The following defines a new function. If the optional "public" keyword is present, the function will be accessible from outside the module

*/

public def factorial(n) { // Dynamic typing

if (n <= 1) {

1 // No return keyword, no ";" at the end of the last line

} else { // else is mandatory

n * factorial(n - 1) // infix operators, recursion

}

}

// There is no main function, just write the program at the end (Python-like)

let num = 5; // mandatory ";" for multiline instructions

factorial(5) // Function call

04-factorial.yml

incarnation: protelis

network-model:

type: EuclideanDistance

parameters: [10]

displacements:

- in:

type: Circle

parameters: [500, 0, 0, 50]

programs:

-

- time-distribution: 1

program: tutorial:factorial

- program: send

- Run with:

./gradlew -Pfile=04-factorial

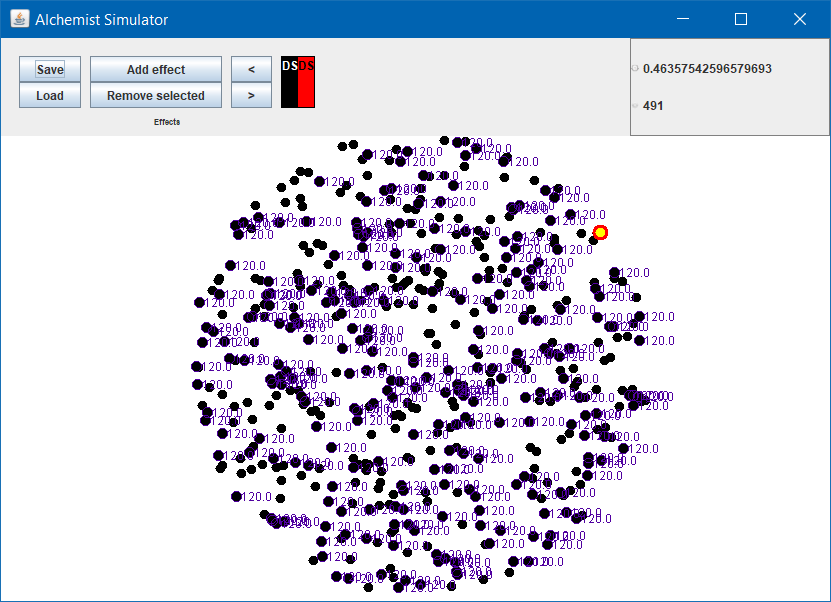

Expected result

- All network nodes independently compute the result

- Those which computed get a purple circle around

- The value of the computation gets written aside them

Higher order, lambdas, tuples, Java interoperability

tutorial/randomfactorial.pt

module tutorial:randomfactorial

import java.lang.Math.random // Import java static methods

def dice() {

let rand = random(); // call methods as if they were local functions

(6 * rand).intValue() // Java-style method invocation on target objects

}

def factorial(n) {

if (n <= 1) { 1 } else { n * factorial(n - 1) }

}

def callWithDice(fun) { // Higher-order function

let num = dice();

fun.apply(num)

}

[ // Use square brackets to build a tuple

callWithDice(factorial), // higher-order call

callWithDice((n) -> {n ^ 2}) // as above, but with an anonymous function (square)

] * [ 1, 2 ] // Tuple can be used with operators (they must have the same length though)

/* Elements of a tuple can be accessed using get(), several methods allow to create new tuples using existing ones. Refer to this javadoc: http://protelis-doc.surge.sh/ */

05-higherorder.yml

incarnation: protelis

network-model:

type: EuclideanDistance

parameters: [10]

displacements:

- in:

type: Circle

parameters: [500, 0, 0, 50]

programs:

-

- time-distribution: 1

program: tutorial:randomfactorial

- program: send

- Run with:

./gradlew -Pfile=05-higherorder

Accessing the device, sensing, actuating

tutorial/deviceaccess.pt

module tutorial:deviceaccess

/*

* Two important entities:

* - self: provides access to the device implementation. Different devices have different capabilities, so some Protelis code may not be able to run on some platforms (e.g. code requiring access to the current coordinates may not work in a device implementation that does not expose such information). See ExecutionContext and its sub-interfaces at http://protelis-doc.surge.sh/org/protelis/vm/ExecutionContext.html

* - env: provides access by name to sensors/actuators. They are treated uniformly as variables, similarly as accessing a map

*/

let injected = if (env.has("value")) { env.get("value") } else { "No value" }; // Read a value, if present

env.put("a generated value",

(100 * self.nextRandomDouble()).intValue()); // This is the best way to ask the platform for a random

self.getDeviceUID().getId() // The unique identifier of this device

06-deviceaccess.yml

incarnation: protelis

network-model:

type: EuclideanDistance

parameters: [10]

displacements:

- in:

type: Circle

parameters: [500, 0, 0, 50]

programs:

-

- time-distribution: 1

program: tutorial:deviceaccess

- program: send

contents: #in this section we can pre-configure the value of sensors

- in: # Optionally, we can limit the area of space where to inject such value

type: Rectangle

parameters: [0, 0, 100, 100]

molecule: value # name of the sensor

concentration: "somevalue" # initial value (any type)

- Run with:

./gradlew -Pfile=06-deviceaccess

Evolving fields with time

- We only computed in a stateless fashion

- No, using env as a mean to retain state is not a good idea

- In field calculus, evolving fields are built with the rep operator

Syntax and semantics in Protelis

rep (value <- initial) { body }

- When

repis encountered for the first time, value is set toinitial - Then

bodyis evaluated, and the result stored invalue - So, in the next round,

valuewill have the result of the evaluation ofbodyin the previous round

A reset counter

primitives/counter.pt

module primitives:counter

public def cyclicCounter(min, max) {

// Let's start from min - 1, so that at the first round we get min.

rep(count <- min - 1) {

// mux is a functional multiplexer: evaluates both branches and returns one of them

mux(count >= max) { // Here == would suffice

0

} else {

count + 1

}

}

}

cyclicCounter(0, 10)

07-counter.yml

incarnation: protelis

network-model:

type: EuclideanDistance

parameters: [10]

displacements:

- in:

type: Circle

parameters: [500, 0, 0, 50]

programs:

-

- time-distribution: 1

program: primitives:counter

- program: send

contents:

- Run with:

./gradlew -Pfile=07-counter

08-async.yml

incarnation: protelis

network-model:

type: EuclideanDistance

parameters: [10]

displacements:

- in:

type: Circle

parameters: [500, 0, 0, 50]

programs:

-

- time-distribution: # Check out in the Alchemist Javadocs all the classes implementing "TimeDistribution" if you want a complete overview of what's available

type: ExponentialTime # Markovian-distributed events with rate = 1

parameters: [1]

program: primitives:counter

- program: send

contents:

- Run with:

./gradlew -Pfile=08-async - Devices run with a random (and memoryless) time distribution (variance equal to the mean): very chaotic behavior.

Distribution: view of the field in the local neighborhood

- We did not yet use the communication abilities of our devices

- It’s time to do it!

- In field calculus, fields of fields are built with the

nbroperator- It builds a field of views of a field in the neighborhood

Syntax and semantics in Protelis

nbr(body)

- Evaluates

body - Returns a field containing the mapping between the neighbouring aligned devices (included self) and the value of body at their location

- A device is d0 aligned to another device d1 if, recently enough, d0 executed the same

nbrinstruction d1 is executing, sharing the result with it.

- A device is d0 aligned to another device d1 if, recently enough, d0 executed the same

- Shares the local value of

body

Reduction and manipulation of fields of fields

Reducing fields

- The information on a field is usually reduced to a single value (a field, not a field of fields)

- Such operation is performed by the

hoodbuilt-in functionhood(reduction, defval, fieldExpr) hood PlusSelf(reduction, defval, fieldExpr)Where

reductionis a function of two parameters(T, T)->T,defvalis a value of typeT, andfieldExpra field of fields ofT fieldExpris evaluated- if

PlusSelfis not specified, the local value is discarded reductionis applied to every value- If there is a result it is returned,

defvalis returned otherwise

Built-in hoods

Protelis has a number of hood operations ready to use (every one with its PlusSelf variant)

minHood, minimum of a field, defaultInfinitymaxHood, maximum of a field, default-InfinityanyHood, “or” on a field of booleans, defaultfalseallHood, “and” on a field of booleans, defaulttruesumHood, sum of the values of the field, default0meanHood, mean of the values of the field, defaultNaNunionHood, a tuple with all the values in the field, default[]

Manipulation of fields of fields

- Fields and locals (using the global view: fields of fields and fields) can be used in any operation

- e.g.

nbr(v) + 1will produce as result a field containing for every neighbor the value ofv + 1 - e.g.

nbr(v) + nbr(a)will combine the values neighbor-per-neighbor - it also works for method call:

nbr(anObject).hashCode()will return a field of hash codes

Manipulation and alignment

- Manipulation of fields of fields is possible because the two instructions that can “break the alignment” (rep and if—to be seen soon) cannot return fields of fields

- Fields of fields are * guaranteed to always have the same devices at every step of the execution!

Pace-making counter

primitives/pacemaker.pt

module primitives:pacemaker

import primitives:counter

def max(a, b) { // a max working on anything that is comparable

if (a > b) { a } else { b }

}

def counter() { rep (i <- -1) { i + 1 } } // plain counter

public def pacemaker(min, max) {

let myCount = [counter(), cyclicCounter(min, max)]; // tuple with the count of my rounds and the value of the cyclic counter

rep (count <- myCount) { // pick and store...

maxHood PlusSelf(nbr(max(myCount, count))) // ...the maximum in my neighborhood between the maximum of my count and the maximum i got until now

}.get(1) // we are interested in the second argument of the tuple, the first an implementation detail

}

pacemaker(0, 10)

09-pacemaker.yml

incarnation: protelis

network-model:

type: EuclideanDistance

parameters: [10]

displacements:

- in:

type: Circle

parameters: [500, 0, 0, 50]

programs:

-

- time-distribution:

type: ExponentialTime

parameters: [1]

type: Event # We define the event manually...

actions: # ...because we want to specify a parameter of the Protelis interpreter.

- type: RunProtelisProgram

parameters: ["primitives:pacemaker", 5] # We discard messages after 5 simulated seconds

- program: send

- Run with:

./gradlew -Pfile=09-pacemaker - The fastest device generates a “wave” that pulls up the slow ones!

Gradient: computing distances

primitives/gradient.pt

module primitives:gradient

/*

* Compute the distance to the closest source. The input is a field of booleans, this function computes the distance from the closest device where the field yields true.

*/

public def gradient(source) {

rep (d <- Infinity) { // Start from an infinite distance

mux (source) { // Functional multiplexer (evaluates both branches)

0 // If I am the source, my distance is zero

} else {

minHood(nbr(d) + self.nbrRange()) // The distance is computed as the minimum of the sum of the distance between me and my neighbors, and my neighbors and the source, for each neighbor.

//minHood PlusSelf(nbr(d) + self.nbrRange())

}

}

}

// Let's compute the distance from the device "zero"

gradient(self.getDeviceUID().getId() == 0)

10-gradient.yml

incarnation: protelis

network-model:

type: EuclideanDistance

parameters: [10]

displacements:

- in:

type: Circle

parameters: [500, 0, 0, 50]

programs:

-

- time-distribution: 1

program: primitives:gradient

- program: send

- Run with:

./gradlew -Pfile=10-gradient - The fastest device generates a “wave” that pulls up the slow ones!

- Move the source node around and see what happens!

Domain restriction with if

- In aggregate programming, using

ifhas different consequences than the languages you are used to- It’s not a “flow control” instruction

- It’s a domain restriction instruction

- Devices get separated in two, non communicating, domains

- They lose alignment

- Reasoning at the device level can be very misleading!

Syntax and semantics in Protelis

if(condition) { then } else { otherwise }

- Evaluates

condition - Executes either then or otherwise, depending on the value of condition

- Unexecuted branches lose their state

repsget reset to default

- If one of the branches contains:

nbrrep- a call to a function using the two above

- then the choice between

ifandmuxis paramount!

Screw up the gradient

primitives/brokengradient.pt

module primitives:brokengradient

def gradient(source) {

rep (d <- Infinity) {

if (source) { // Changed mux with if

0

} else {

// The source never enters this domain!

// Frome the single device perspective, it never executes this branch, and so it never shares its knowledge of being a source!

minHood(nbr(d) + self.nbrRange())

}

}

}

gradient(self.getDeviceUID().getId() == 0)

11-brokengradient.yml

incarnation: protelis

network-model:

type: EuclideanDistance

parameters: [10]

displacements:

- in:

type: Circle

parameters: [500, 0, 0, 50]

programs:

-

- time-distribution: 1

program: primitives:brokengradient

- program: send

- Run with:

./gradlew -Pfile=11-brokengradient - Our toy got bricked!

Mixing rep, if and mux

primitives/twocounters.pt

module primitives:twocounters

def counter() { rep(c <- 0) { c + 1 } }

[

if (counter() % 2 == 0) { counter() } else { counter() },

mux (counter() % 2 == 0) { counter() } else { counter() }

]

12-twocounters.yml

incarnation: protelis

network-model:

type: EuclideanDistance

parameters: [10]

displacements:

- in:

type: Circle

parameters: [500, 0, 0, 50]

programs:

-

- time-distribution: 1

program: primitives:twocounters

- program: send

- Run with:

./gradlew -Pfile=12-twocounters ifcontinuously resets therepstatus!

Gradient in a sub-domain

primitives/gradobs.pt

module primitives:gradobs

import primitives:gradient

if (env.has("obstacle")) {

Infinity

} else {

gradient(self.getDeviceUID().getId() == 0)

}

13-gradobs.yml

incarnation: protelis

network-model:

type: EuclideanDistance

parameters: [10]

displacements:

- in:

type: Circle

parameters: [500, 0, 0, 50]

programs:

-

- time-distribution: 1

program: primitives:gradobs

- program: send

contents:

- in:

type: Rectangle

parameters: [-15, -50, 30, 75]

molecule: obstacle

concentration: true

- Run with:

./gradlew -Pfile=13-gradobs - Expected:

- Modify the program to use mux, and see the difference!

Raise the abstraction level

- Programming in terms of

rep,nbrandifis very, very low level- And also, very much error-prone

- What would happen if

minHoodPlusSelfwas used in the gradient?- Try it in the simulator, modifying the 10-gradient example

- Move nodes around: it’s not self-stabilizing anymore…

- Several coordination patterns are common to many algorithms

- Spread information

- Accumulate information

- Evolve state with time

- Partition the system

- We want to program with them directly

- There are several ways of implementing such primitives

- With different properties, both functional and non-functional

The G / C / T / S building blocks

G: spreading information

G(source, initial, metric, accumulate)

- Spreads

initialfrom source initialcan be of any type (T)sourceis a booleanmetric is a function()->Field<Number>that computes the gradient variation (the same role played bynbrRangein ourgradient)valuesare combined withaccumulate, a function(T)->T

Example: rewrite the gradient with G

def distanceTo(source) {

let metric = () -> { self.nbrRange() };

G(source, 0, metric, v -> { v + metric.apply()})

}

C: accumulate information

C(potential, reduce, local, null)

- Accumulates

localvalues along apotential potentialis aComparabletype (typically a number)reduceis a(T, T) -> Tlocalis the local value (T)nullis the default value, in case there is nothing to accumulate

Example: Count the devices in the system, accumulating the information in source

def countDevices(source) {

C(distanceTo(source), sum, 1, 0)

}

T: evolve state

T(initial, zero, decay)

- A timer from initial to zero with a decay rate.

S: partition the network

S(grain, metric)

- Elects a leader every grain, using the provided metric.

- Returns a boolean (true if the node is a leader)

grainis a number with the partition sizemetricis a()->Field<Number>that computes the distances- A timer from

initialtozerowith adecayrate.

advanced/voronoi.pt

module advanced:voronoi

import protelis:coord:sparsechoice

import protelis:coord:spreading

let metric = () -> { self.nbrRange() };

G(S(25, metric), 0, metric, v -> { v + metric.apply() })

- It’s one line of “true” code

14-voronoi.yml

incarnation: protelis

network-model:

type: EuclideanDistance

parameters: [10]

displacements:

- in:

type: Circle

parameters: [500, 0, 0, 50]

programs:

-

- time-distribution: 1

program: advanced:voronoi

- program: send

- Run with:

./gradlew -Pfile=14-voronoi - Try to move the nodes around, and see how the system adapts!

Limitations of the building block

- Programming with building blocks is way easier than fiddling with

reps andnbrs by hand - …but it is not yet where we’d like to stand!

- Many “useful” behaviors can’t be captured

- as they are not self-stabilizing

- Yet, they can be of use in many situations

- Think of gossip, for instance

- It’s very hard to get a grasp of the global situation

- If there is an information spread from multiple sources, only

- information from the closest would make it

- This is ok in many situations

- But not enough in others

- Many algorithms recur very often

- They should stay in a library

Use protelis-lang and focus on the application code

protelis-lang is a library intended to:

- Provide a collection of the most widely used distributed algorithms

- Contains over a hundred of them, from literature and other tools

- If you develop something new, contribution is very welcome :)

- Shift the focus of the designer entirely on application code

- Provide means to overcome the limitations of the building blocks

- Through a number of meta-algorithms that allow parallel aligned executions

- Mainly by means of the novel

multiInstancealgorithmprotelis-langis part of the Protelis distribution and ready to use

This library was first introduced in 2017 at a SASO Workshop: the 2nd edition of eCAS.

Partition the network and spread multiple gradients

advanced/summarize.pt

module advanced:summarize

import protelis:lang:utils

import protelis:coord:spreading

import protelis:coord:sparsechoice

import protelis:coord:accumulation

import protelis:state:time

// Let's simulate a sensor measuring the temperature (in Celsius, range 20 to 30) every minute

env.put("temp", rep (v <- 25) { if(cyclicTimer(60)) { 20 + self.nextRandomDouble() * 10 } else { v }});

// Let's compute the mean temperature of the whole network and share th infomation to all devices

let sink = S(Infinity, nbrRange);

summarize(sink, sum, env.get("temp"), 0) / broadcast(sink, countDevices(distanceTo(sink)))

15-summarize.yml

incarnation: protelis

network-model:

type: EuclideanDistance

parameters: [10]

displacements:

- in:

type: Circle

parameters: [500, 0, 0, 50]

programs:

-

- time-distribution: 1

program: advanced:summarize

- program: send

- Run with:

./gradlew -Pfile=15-summarize

Brownian movement

16-brownian.yml

incarnation: protelis

network-model: { type: EuclideanDistance, parameters: [10] } # Compact syntax

program-pools:

- compute-gradient: &gradient #This is a YAML anchor: assigns a name to this YAML object, and can be reused later in the file. It's not an Alchemist thing, it's pure YAML specification

- time-distribution: 1

program: primitives:gradient

- program: send

- move: &move

- time-distribution: { type: ExponentialTime, parameters: [1] }

type: Event

actions:

- { type: BrownianMove, parameters: [1] }

displacements:

- in: { type: Circle, parameters: [500, 0, 0, 50] }

programs:

# Now maybe the strange double list in "programs" makes sense :)

- *gradient # Reference to the anchor previously defined.

- *move

- Run with:

./gradlew -Pfile=16-brownian

Controlling the movement direction

advanced/converge.pt

module advanced:converge

import protelis:coord:sparsechoice

import protelis:coord:spreading

import protelis:state:time

let leader = S(25, nbrRange);

let destination = broadcast(leader, self.getCoordinates());

destination = if (isSignalStable(destination, 10)) { destination } else { self.getCoordinates() };

env.put("destination", destination);

self.getCoordinates() == destination

17-converge.yml

incarnation: protelis

network-model: { type: EuclideanDistance, parameters: [10] }

program-pools:

- compute-gradient: &gradient

- time-distribution: 1

program: advanced:converge

- program: send

- move: &move

- time-distribution: { type: ExponentialTime, parameters: [1] }

type: Event

actions:

- { type: MoveToTarget, parameters: [destination, 1] }

displacements:

- in: { type: Circle, parameters: [500, 0, 0, 50] }

programs:

- *gradient

- *move

- Run with:

./gradlew -Pfile=17-converge

Exporting data

18-export.yml

incarnation: protelis

network-model: { type: EuclideanDistance, parameters: [10] }

program-pools:

- compute-gradient: &gradient

- { time-distribution: 1, program: "advanced:converge" }

- program: send

- move: &move

- time-distribution: { type: ExponentialTime, parameters: [1] }

type: Event

actions: [ { type: MoveToTarget, parameters: [destination, 1] } ]

displacements: [ { in: { type: Circle, parameters: [500, 0, 0, 50] }, programs: [*gradient, *move] } ]

export:

- time # Exports the current time

- number-of-nodes # Exports the number of nodes in the system

- molecule: advanced:converge # The name of the sensor / actuator whose value will be exported

# Optionally, a "property: program" section can be specified, where "program" is a valid chunk of protelis code. The sensor value will be processed using such code before being exported.

value-filter: onlyfinite # You may want to keep poisonous values (Infinities and NaN) from being exported or passed to the aggregator. Available filters are "nofilter" (default), "onlyfinite" (discards both NaN and Infinities), "filternan", "filterinfinity".

aggregators: [sum, mean, kurtosis] # The aggregator takes all the data from nodes and reduces it to a single value. If omitted, one value per node will be exported (in this case, 500 columns...). You can load any UnivariateStatistics from the Apache Commons Math library, just by their name.

- Run with:

./gradlew -Pfile=18-export - Look at the file

exported-data.txt

Using variables and controlling randomness

19-variables.yml

incarnation: protelis

variables:

seed: &seed # You can give the anchor any name, assigning the name of the variable is convenient, though

{min: 0, max: 9, step: 1, default: 0} # This variable ranges in [0, 9], steps of 1, defaulting to 0

connection-radius: &connection-radius

formula: 10 # An instance of a Javascript interpreter is created to evaluate the expression.

round-frequency: &round-frequency

formula: Math.max($seed, 1) # Other variables can be referred by prefixing them with $ (e.g. $seed would be substituted by the current value of seed).

language: scala # The system defaults to Javascript, but a Scala interpreter can be instanced instead

program-name: &program-name

formula: "'advanced:converge'" # Use whatever type you want - just make sure you use them properly

seeds:

scenario: *seed # This controls the initial displacement of the nodes

simulation: *seed # This controls the generated event times

network-model: { type: EuclideanDistance, parameters: [*connection-radius] }

program-pools:

- compute-gradient: &gradient

- { time-distribution: 1, program: *program-name }

- program: send

- move: &move

- time-distribution: { type: ExponentialTime, parameters: [*round-frequency] }

type: Event

actions: [ { type: MoveToTarget, parameters: [destination, 1] } ]

displacements: [ { in: { type: Circle, parameters: [500, 0, 0, 50] }, programs: [*gradient, *move] } ]

- Run with:

./gradlew -Pfile=19-variables - Run it again changing the default for the

seedvariable! - Variables can be instanced with the type/parameters syntax

- Several implementations available (geometrically scaling, arbitrary values…)

- See http://alchemist-doc.surge.sh/it/unibo/alchemist/loader/variables/package-frame.html

Batches

Independent variables (those with no formula entry) define the batch content

- if Alchemist is executed with the

--batch, it will run in headless mode, spawning a simulation for each possible combination of values of the variables listed after the -var option - e.g.:

java -jar alchemist.jar --batch --var seed range- If range may yield 1, 10 or 100 and seed may yield 0 or 1

- Six simulations would get generated

- Don’t abuse: with many variables and many variables thing get big very quickly

- Simulations are executed in parallel

- By default one simulation per core + 1

- This behavior is configurable with a command line option

- A grid executor is in our TODO list

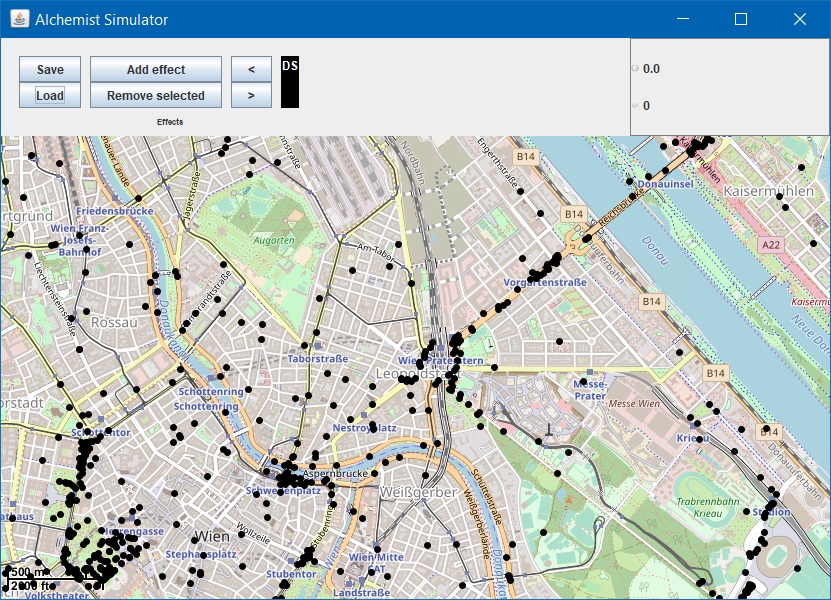

Loading maps

20-maps.yml

incarnation: protelis

environment:

type: OSMEnvironment

parameters: ["/vcm.pbf"] # Loads from classpath, an absolute path to the file would work as well

pools:

- pool: &move

- time-distribution: 0.1

type: Event

actions:

- type: ReproduceGPSTrace # Other strategies are available, such as interpolate the track using pedestrian roads

parameters: ["/vcmuser.gpx", false, "AlignToTime", 1365922800, false, false]

displacements:

- in:

type: FromGPSTrace # displace nodes as they are in the GPS track

parameters: [1497, "/vcmuser.gpx", false, "AlignToTime", 1365922800, false, false]

programs:

- *move

- Run with:

./gradlew -Pfile=20-maps